Safeway is no longer the company it was just nine months ago, and it is continuing to evolve.

Less than a year after Steve Burd retired as chairman, president and CEO, Safeway has sold off its Canadian division, discontinued its Dominick’s operation in Chicago and initiated a variety of operational changes while possibly considering further asset sales — all part of the company’s commitment to increase shareholder value under Robert Edwards, Burd’s successor as president and CEO.

“Safeway is looking at every possibility, and there are few sacred cows,” Karen Short, senior analyst at Deutsche Bank, New York, said. “Whatever would generate the most shareholder value would be an option.”

Neil Stern, senior partner at McMillanDoolittle, Chicago, said most of the changes at Safeway over the next year are likely to be internal.

“Selling Canada has provided Safeway with enough capital to try to turn things around without selling more assets, and discontinuing Dominick’s has eliminated a big drag on cash flow,” he told SN.

“The challenge now is to grow sales and profitability through pricing strategies, merchandising adjustments and promotional programs — all internal tools.”

Safeway declined to comment to SN for this article.

According to Chuck Cerankosky, managing director at Northcoast Research, Cleveland, Burd obviously had a hand in the decision to sell Canada, since the sale — for $5.8 billion — was concluded only about a month after Burd retired.

“Obviously that deal took months to negotiate and was driven by an unexpectedly generous price that Sobeys was willing to pay,” he told SN. “Most people thought Safeway would hang onto Canada because no one thought it would get so much money for the division.”

Cerankosky said the sale a couple of years ago of Genuardi’s, in the Philadelphia market, combined with the sale of Canada in mid-2013 and the writedown of Dominick’s at year’s end, “buys Safeway some time to review its strategic makeup.”

Kelly Bania, a research analyst for BMO Capital Markets, New York, said Safeway is taking a more targeted approach to individual customers, “[putting] less emphasis on the more historical one-size-fits-all approach” and opting instead to cluster stores based on demographic or ethnic patterns — a strategy Bania said could “aid Safeway in capturing a larger share of the customer’s wallet.”

Meredith Adler, managing director for Barclays Capital, New York, said Edwards has acknowledged that Safeway has “serious fundamental weaknesses,” and despite his intention to take steps to create additional shareholder value, she said she remains skeptical “that meaningful improvements can be achieved any time soon.”

Meredith Adler, managing director for Barclays Capital, New York, said Edwards has acknowledged that Safeway has “serious fundamental weaknesses,” and despite his intention to take steps to create additional shareholder value, she said she remains skeptical “that meaningful improvements can be achieved any time soon.”

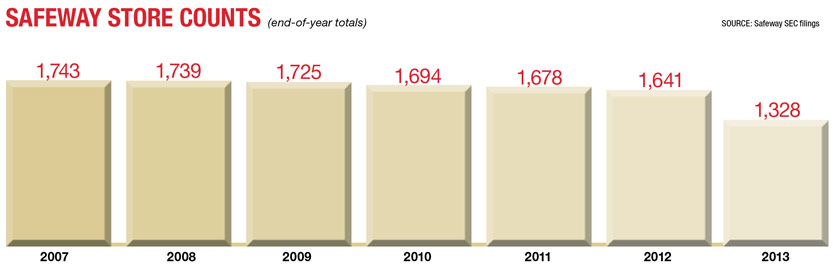

Following the Canadian sale and the exit from its Chicago operation, Safeway sales — for just over 1,400 stores — are estimated at $37.3 billion for the fiscal year that ended Dec. 29.

The sale of the Canadian division has left Safeway with proceeds of approximately $4 billion on its balance sheet — half of which is earmarked for debt reduction, with another $1.8 billion for share repurchases and $200 million for investments in growth opportunities, observers said.

The presence of $4 billion of unspent cash on the chain’s books has piqued interest from private-equity buyers, who view Safeway as a possible takeout target. Adding to industry speculation about what Safeway might do were reports in the fall the chain had hired Goldman Sachs to help it explore its options.

Within days of that speculation, Safeway announced it was seeking buyers for Dominick’s — a chain whose market share had reportedly fallen to 9%, compared with 23% in 2000, two years after Safeway acquired it in 1998.

Observers said part of Safeway’s motivation for disposing of the chain may have been to offset a portion of the $1.89 million in capital-gains tax created by the sale of Canada.

Read more: Sign up here for SN’s free daily e-newsletter and others

The decision to sell Dominick’s was “a great first step” for Safeway to improve its operations, Scott Mushkin, managing director at Wolfe Research, New York, pointed out, “because it will yield $400 million to $450 million in tax savings, which will mitigate the gain on the Canada sale.”

According to Adler, “Safeway would almost have an incentive to dispose of [additional] assets at a low price since that would allow it to offset more of the gain from the sale of Canada. It would not be a surprise if the company had tried to sell these [assets] before without success, but it is only now that the sale price might not matter.”

Other changes

Besides the sale of Canada and the exit from Chicago, Safeway is making other moves that set the Edwards era apart from the Burd era, observers said, including the following:

• Putting more emphasis on sales growth and less on expense controls and margin growth.

• Targeting programs to local demographics — including giving more autonomy to local managers — in place of the chain’s “one-size-fits-all” approach that created consumer disaffection in Philadelphia, Chicago and Texas.

• Abandoning implementation of the wellness initiative that Burd once said would transform the industry.

• Considering options to sell additional assets and become a Western-focused company.

Burd’s legacy has not been dismissed, Stern said, pointing to the operational efficiencies, marketing initiatives and private label programs Burd put in place. “No one is bashing Burd, but there were things that needed to be fixed, and the company is now engaged in a balancing act to fix those things while also getting rid of some of the things Burd was not willing to deal with.

“Clearly Edwards is very focused on looking at the returns of all Safeway divisions, and one of the benefits of having that large amount of cash on the books from the sale of Canada is that it allows Safeway to strengthen its balance sheet and buy back stock and possibly look at selective acquisitions of additional store sites in existing markets, to strengthen its position in those markets.”

“Clearly Edwards is very focused on looking at the returns of all Safeway divisions, and one of the benefits of having that large amount of cash on the books from the sale of Canada is that it allows Safeway to strengthen its balance sheet and buy back stock and possibly look at selective acquisitions of additional store sites in existing markets, to strengthen its position in those markets.”

Few of the changes that occurred in the second half of 2013 seemed likely last May when Burd retired after more than 20 years at the helm and was succeeded by Edwards, the chain’s CFO.

“At the time it felt like Steve Burd had hand-picked a successor from inside the company who would follow the same path he had followed. Because Edwards was not an outsider, his promotion did not signal any change, and most observers anticipated more of the same,” said Stern.

“But Edwards has surprised some people with the aggressiveness of the changes he has made, particularly deciding to sell physical assets. The feeling at Safeway now is that some pretty substantial changes are needed, and it’s almost as if Edwards was lying in wait to make some of those changes.

“But Edwards has surprised some people with the aggressiveness of the changes he has made, particularly deciding to sell physical assets. The feeling at Safeway now is that some pretty substantial changes are needed, and it’s almost as if Edwards was lying in wait to make some of those changes.

“The most visible things Edwards has done is dismantling portions of the company that Safeway had acquired under Burd, particularly Dominick’s. Some of that is probably something Burd himself should have done, though it’s awfully hard for an incumbent CEO to sell one of his ‘babies.’ It’s much easier for the next guy to do it.”

Edwards has also set aside the wellness initiative Burd had heralded in the months prior to his retirement as a major game-changer, Stern noted — though it was never clear exactly what that initiative entailed, he noted.

“Whatever it was, it was apparently not ready for prime time,” he said.

Executive changes

Edwards may also be planning several executive changes at the corporate and division levels, Stern added, noting that the first indication of those intentions may have been the departure in December of the top three executives in Safeway’s Eastern division.

According to Mushkin, Edwards is altering Safeway’s basic focus — empowering store managers and adjusting pricing and merchandising to fit local demographics, thereby lessening the command and control structure from corporate “that created a one-size-fits-all dynamic.

“These changes, while not revolutionary, should, if executed properly, help improve sales,” he added.

Cerankosky said Edwards’ financial background “means he understands that merchants at the banner level — and the neighborhood level — have a lot of insights about what merchandising should look like.

“Whereas Burd was more interested in centralizing merchandising and marketing, Edwards’ moves to go local would give Safeway some latitude in moving away from that approach, and that could be significant. But it’s not clear at this point if the division guys can handle the responsibilities for promoting, pricing and assortment, and it will take awhile to see the results of trying that approach.”

Bania said Edwards’ decision to relax the company’s tight shrink targets in favor of supporting better sales “[is] a shift in strategy [that] remains a positive for the company, particularly given a growing focus on fresh categories from consumers.”

According to Mushkin, Edwards appears to be “laser-focused on driving sales and profit dollars rather than expense control and margin rates, whereas Safeway [under Burd] had previously focused too often on short-term margin gain and earnings, resulting many times in long-term business pain.

Read more: SN's Power 50 profile of Safeway CEO Robert Edward

“While this short-term change could nip margin rates, the long-term benefits are significant from the perspectives of market share, asset productivity and earnings. Edwards’ forceful move to sales first and profits next is the right strategy.”

Mushkin said monetizing non-core areas and reinvesting in core geographies is “vitally important for Safeway to [achieve] operational success. A move toward higher market share undoubtedly will have positive implications both on sales and margins.”

Edwards also wants to tailor each store to its local market based on income and demographics, Mushkin noted — a move it has already made at about 300 high-end stores, with a similar rollout for Hispanic stores also under way.

Bania said initiatives to cluster premium and Hispanic stores have already proven successful, with those stores “significantly outperform[ing] average non-fuel ID sales.”

Selling divisions

Several industry observers believe Safeway is interested in selling more divisions to maximize shareholder value after selling Canada and exiting Chicago.

Andrew Wolf, Boston-based managing director for BB&T Capital Markets, Richmond, Va., offered two possible scenarios:

• In the first — the less likely option, he noted — Safeway could sell the entire company for a price he estimated at $10 billion. (Separately, Mushkin of Wolfe Research estimated the price could be about $10.8 billion, plus approximately $1.1 billion for the chain’s 73% share of Blackhawk.)

• In an alternative scenario, Safeway could opt to sell its least productive assets while keeping the best operations, then work to improve returns at those divisions “to achieve fundamental momentum over time,” Wolf said.

“There’s been a shift in thinking [at the chain] that seems to suggest Safeway will consider divesting some of its weaker divisions to re-trench and right-size the business and focus on the West, where it is strongest,” he explained.

Observers said they believe Safeway could ultimately decide to divest divisions in Phoenix, Denver, Texas and the Washington D.C. area and become a regional player along the West Coast — holding on to operations in Northern California, Southern California (where it operates under the Vons banner), Portland, Ore., and Seattle (including Alaska), which would leave it with just under 900 stores and sales of about $23 billion.

Observers said they believe Safeway could ultimately decide to divest divisions in Phoenix, Denver, Texas and the Washington D.C. area and become a regional player along the West Coast — holding on to operations in Northern California, Southern California (where it operates under the Vons banner), Portland, Ore., and Seattle (including Alaska), which would leave it with just under 900 stores and sales of about $23 billion.

According to Cerankosky of Northcoast Research, “I’ve always felt it would make sense for Safeway to focus on its stores west of the Rockies, including Denver, so it’s possible, now that the Texas and Eastern divisions are so isolated from a marketing and logistics standpoint, that it might make sense to consider getting rid of them.”

SN INSIGHT

Since Steve Burd retired last May as chairman, president and CEO of the Pleasanton, Calif.-based chain, the company has sold off its Canadian division, discontinued its Dominick’s operation in Chicago and initiated several operational changes — all under the direction of Robert Edwards, Burd’s successor as president and CEO. The changes include:

- Putting more emphasis on sales growth and less on expense controls and margin growth.

- Targeting programs to local demographics — including giving more autonomy to local managers — in place of the chain’s “one-size-fits-all” approach.

- Abandoning implementation of the wellness initiative that Burd once said would transform the industry.

- Considering options to sell additional assets and become a Western-focused company.

— Elliot Zwiebach

Speculation arose in October that Cerberus Capital Management, the New York-based investor that owns Albertsons, might be interested in acquiring Safeway.

“Combining the two would create a dominant Western grocer” with significant synergies and economies of scale, Mushkin said.

“While there would be some concerns by the Federal Trade Commission in Southern California, the combination would boost local market shares [in all sections of the country], which is important for scale, and add adjacent markets.”

Cerankosky said some kind of deal with Cerberus is possible, noting the two companies “have already had some conversations because Safeway sold four of its Dominick’s stores to Cerberus. But Cerberus has some stores that may not fit into its long-term plans, and it wouldn’t be a surprise if Safeway and Cerberus or Safeway and some other companies did some location-swapping to help boost industry consolidation.”

According to Mushkin, a Safeway-Cerberus union would boost Safeway’s market share position in all divisions, giving it the No. 1 market share in Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Seattle; keeping it at No. 1 in San Francisco and Portland, Ore.; and moving it up to No. 2 in Phoenix and Denver (behind Kroger), as well as Dallas (behind Walmart).

The combination of Safeway’s Eastern division with Cerberus would also boost the two companies’ shares in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and New England, he added — making Safeway-Cerberus No. 2 in Washington D.C. and Baltimore (behind Ahold); and No. 3 in both Philadelphia (behind Wakefern and Ahold) and Boston (behind Ahold and Demoulas).

Industry sources said Texas, like Chicago, has been a tough market for Safeway, with market shares at its Randalls chain in Houston down to 6% from 12% in 2000, and Tom Thumb’s share in Dallas at 10%, down from 18% in 2000.

“The Randalls stores are a good size and located in relatively affluent areas,” Adler of Barclays said. “The Tom Thumb stores are small, though their locations are very good [and] they serve dense and affluent parts of Dallas.”

Since neither Randalls nor Tom Thumb is unionized, selling them could be a bit easier than selling stores in some other divisions, she noted. “Nonetheless, Safeway might have an incentive to accept a low price or even close the stores [in some divisions] entirely,” Adler pointed out.

Mushkin said he expects additional divestitures, but he also anticipates “some purchases that can bolster stronger geographies.”

Sidebar: Just for U needs work, observers say

According to Neil Stern, managing partner at Chicago-based McMilllanDoolittle, one program that needs some review is Just for U, Safeway’s digital pricing initiative that offers coupons and reduced pricing to customers willing to spend time on their computers to find them.

Just for U puts pricing within approximately 10% of Walmart and is being used by approximately 20% of households, though those households represent a higher percentage of sales, observers said.

“Penetration of those savings needs to be higher,” said Scott Mushkin, an analyst at Wolfe Research “Right now, Just for U is overly dependent on consumers’ willingness to overtly engage with the program, [which] makes Just for U fairly ineffective when it comes both to attracting additional consumers and converting less loyal customers into core shoppers.

“Penetration of those savings needs to be higher,” said Scott Mushkin, an analyst at Wolfe Research “Right now, Just for U is overly dependent on consumers’ willingness to overtly engage with the program, [which] makes Just for U fairly ineffective when it comes both to attracting additional consumers and converting less loyal customers into core shoppers.

“The good news is the company [might] be willing to add some ‘push’ features to the Just for U program.”

For Stern, the program requires too much work by consumers, “without enough visible value attached,” he explained. “Even if a customer downloads offers from the computer to his loyalty card, there are other offers at shelf level that make it confusing to track the benefits a customer is getting from Just for U.

“So Safeway needs to work on simplifying that program and making its pricing strategy clearer for customers so they understand the value of shopping at Safeway.”

According to Chuck Cerankosky, an analyst at Cleveland-based Northcoast Research, Just for U is “an evolving concept that should change as customers use it more.”

“It took Kroger several years to make a success of its relationship with Dunnhumby, and it’s going to take awhile for Safeway to make its Just for U program work. At this point it’s still not clear if the program is driving loyalty or just cherry-picking.”

For Mushkin, the problem with Just for U “is that too few of its users fall into the [fully-engaged] category, leaving the majority of customers with prices that are generally above the competition,” he said. “Safeway needs to address this issue.”

| Suggested Categories | More from Supermarketnews |

|

|

|

|